Cool tool: Cross Validation is the Stack Overflow for statistics questions.

The utility of using neuroscience to understand art (e.g. "neuroaesthetics") is considered.

Cool: the Wounded Warrior Bill mandates cognitive testing of soliders before and after deployment. This can help screen for brain injuries and (in theory) get wounded soliders needed treatment. Not cool: this is not actually happening.

Ireland is considering a proposal to add lithium to the drinking water as a method for reducing crime. Lithium is a standard treatment for bipolar disorder. The proposal cites studies in Texas and Japan showing reduced crime in locations where lithium is present in drinking water (though it's not clear whether it was added on purpose, like fluoride).

Mind Hacks follows a new amendment to the US Controlled Substances act, adding a number of chemically synthesized cannabinoids.

"...the raison d’être of a college is to nourish a world of intellectual culture; that is, a world of ideas, dedicated to what we can know scientifically, understand humanistically, or express artistically. "

A beautiful critique of statistical cut-corners in the Freakonomics empire.

The Neurocritic discusses an interesting case: a child with a malformation in the prefrontal cortex and extreme behavioral problems. Can we assign a causal relation?

Sunday, December 18, 2011

Friday, December 16, 2011

Who takes the responsibility for quality higher education?

This gives me chills: a professor denied tenure for using the Socratic method of teaching. Of course, there are two sides to every story and this article is rather one sided - I have been in classes where so-called Socratic methods are thinly veiled excuses for hurling insults at students - but if we are to take the article at face value, this is another story in a disturbing educational trend.

The Socratic method is challenging for students and requires preparation and engagement with the material. It requires being able to effectively communicate under pressure. However, I feel that learning involves a certain amount of discomfort. Learning means pushing past the boundaries of what we already know, and what we can already do. Most undergraduate courses I took were of lecture-style, teaching students to expect to be a passive audience in class. It's a much easier route and the student can hide lack of preparation, misunderstanding or having a bad day. However, these students cannot hide forever, and this under-preparation often comes back to haunt them at exam time.

As a TA in graduate school, I saw many freshmen having harsh wake-up calls when the first midterms came back. The typical story was "But I came to all the classes, and I read the book chapters twice! How could I have gotten a C on the exam???" The unfortunate answer is that the student mistakes being able to parrot back a section of textbook or lecture for understanding the material. When an exam forces the student to use this information in an analytic or synthetic way, the facade of learning crumbles.

I don't know any instructor who wants to give a student a poor grade, but the integrity of the educational system depends on accurate assessment of mastery. If an instructor is fired, demoted or denied tenure due to the rigors of his/her course, this could spell the end of education. Sadly, this story is reminiscent of this case: a professor denied tenure for not passing enough students. I highly recommend reading this page because, if we are to take the author at his words, he took every reasonable action to enable his students to succeed.

Who is responsible for student success in higher education? Professors, of course need to be responsible for presenting learning opportunities to students in a clear manner, and to be available for advice and guidance at office hours. However, university students are adults and need to take responsibility for the ultimate learning outcomes. I am concerned by a culture of entitlement that has conditioned students to expect top marks for simply showing up. The expectations of the "self-esteem generation" and the incentives of professors to earn high student evaluations both play a role, I suspect.

I wonder sometimes whether the cost of attendance at American colleges and universities partially drives this phenomenon. Paying for education turns students and their families into customers, and "customers are always right". Perhaps subsidizing higher education would create a culture that divorces education from "service", leading to more honest evaluations and better learning.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Soundbites: Thanksgiving edition

It was my birthday this week. Turns out my brain is just about done maturing. (Tell that to my behavior...)

Not really news: tenured faculty members bring in twice as much money to universities as they cost.

Funny titles for scientific studies.

You know how I'm often griping about the lack of published negative results and replication attempts? Some people are trying to solve both. Very cool.

From Nature: improving understanding of statistical arguments.

EEG can be used to predict conscious awareness in vegetative patients.

Wanna take some computer science courses at Stanford? Several courses will be open to the public virtually next quarter!

The results of another self-reported survey on the use of cognitive enhancing drugs.

Not really news: tenured faculty members bring in twice as much money to universities as they cost.

Funny titles for scientific studies.

You know how I'm often griping about the lack of published negative results and replication attempts? Some people are trying to solve both. Very cool.

From Nature: improving understanding of statistical arguments.

EEG can be used to predict conscious awareness in vegetative patients.

Wanna take some computer science courses at Stanford? Several courses will be open to the public virtually next quarter!

The results of another self-reported survey on the use of cognitive enhancing drugs.

Monday, October 31, 2011

Soundbites: Spooky edition

Should we give all surgeons cognitive enhancers to improve performance?

The "smart phone brain scanner". This could either be the best thing ever, or the worst thing.... I still have not decided.

The Royal Society has made 60,000 articles freely accessible. W00t!

... happy birthday, dear fMRI. Happy 20th birthday to you!

New ADHD guidelines allow for diagnosis in children as young as 4. (Which to me begs the question of what a "normal" 4 year old is supposed to act like).

What counts as a person in an era where some states are proposing laws to define a fertilized egg as a person? Neuroethics Canada has some intelligent commentary.

The "smart phone brain scanner". This could either be the best thing ever, or the worst thing.... I still have not decided.

The Royal Society has made 60,000 articles freely accessible. W00t!

... happy birthday, dear fMRI. Happy 20th birthday to you!

New ADHD guidelines allow for diagnosis in children as young as 4. (Which to me begs the question of what a "normal" 4 year old is supposed to act like).

What counts as a person in an era where some states are proposing laws to define a fertilized egg as a person? Neuroethics Canada has some intelligent commentary.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Is the academic publishing industry evil?

Like most people, I didn't think much about the profit model for academic journals until I was publishing in them. Even after going through the process a few times, I am still struck by a feeling that academic journals are the toll trolls on the road of knowledge dissemination.

While a non-academic journal such as The Atlantic or the New Yorker pays its authors for content, academic journals get massive amounts of content volunteered to them. While non-academic journals pay an editor to hone and perfect the content, academic journals have volunteer peer reviewers and volunteer action editors doing this work for the cost of a line on the academic CV. Both types of journals offset some publication costs with advertising, but while non-academic journals sell for ~$5 per issue and under $50 for a year's subscription, an academic journal will charge $30-40 per article and thousands for a subscription. This means that the tax payer who funds this research is not able to afford to read the research.

Let's say you're an author, and you're submitting your article to a scientific journal. It gets reviewed and edited, and is accepted for publication by the action editor. Great! Your excitement gets diminished somewhat from two documents that get sent to you: one that signs over your copyright to the journal, and a publishing bill based on the number of pages and color figures in your work (often a few hundred dollars). Now, if you want to use a figure from this article again (say, for your doctoral dissertation), you must write the journal to get permission to use your own figure. Seriously. Other points against academic journals can be found in this entertainingly inflammatory piece.

But what about open access journals? Good question. These journals exist online, and anyone can read them, which is great for small libraries struggling to afford journal costs and citizens wishing to check claims at the source. They're not so great for the academic, who gets slapped with a $1000-2000 fee for publishing in them. As inexpensive as online infrastructure is these days, I would love for someone to explain to me how it costs the journal so much just to host a paper.

I was excited to read this interview with academic publishers Wiley and Elsevier on these issues. However, I find most of the responses to be non-answer run-arounds. A telling exception to this is in the first question "what is your position on Open Access databases?". Wiley responded:

While a non-academic journal such as The Atlantic or the New Yorker pays its authors for content, academic journals get massive amounts of content volunteered to them. While non-academic journals pay an editor to hone and perfect the content, academic journals have volunteer peer reviewers and volunteer action editors doing this work for the cost of a line on the academic CV. Both types of journals offset some publication costs with advertising, but while non-academic journals sell for ~$5 per issue and under $50 for a year's subscription, an academic journal will charge $30-40 per article and thousands for a subscription. This means that the tax payer who funds this research is not able to afford to read the research.

Let's say you're an author, and you're submitting your article to a scientific journal. It gets reviewed and edited, and is accepted for publication by the action editor. Great! Your excitement gets diminished somewhat from two documents that get sent to you: one that signs over your copyright to the journal, and a publishing bill based on the number of pages and color figures in your work (often a few hundred dollars). Now, if you want to use a figure from this article again (say, for your doctoral dissertation), you must write the journal to get permission to use your own figure. Seriously. Other points against academic journals can be found in this entertainingly inflammatory piece.

But what about open access journals? Good question. These journals exist online, and anyone can read them, which is great for small libraries struggling to afford journal costs and citizens wishing to check claims at the source. They're not so great for the academic, who gets slapped with a $1000-2000 fee for publishing in them. As inexpensive as online infrastructure is these days, I would love for someone to explain to me how it costs the journal so much just to host a paper.

I was excited to read this interview with academic publishers Wiley and Elsevier on these issues. However, I find most of the responses to be non-answer run-arounds. A telling exception to this is in the first question "what is your position on Open Access databases?". Wiley responded:

"The decision to submit a manuscript for publication in a peer-review journal reflects the researcher’s desire to obtain credentialing for the work described. The publishing process, from peer review through distribution and enabling discovery, adds value, which is manifest in the final version of the article and formally validates the research and the researcher."

(Emphasis mine).

In other words, we do this because there is a demand for our journal as a brand. You, researcher are creating the demand. However, I do hold out hope that as more publishing moves online, more researchers and librarians realize that there are both diamonds and rough in all journals, and this will wear away at brand prestige, allowing the illusion of "publisher added value" to wear away.

Friday, October 7, 2011

Insula-gate

For those just tuning into this week's latest installment of NeuroNonsense brought to you by the New York Times, let me being you up to date:

The New York Times allowed (nonscientist) Martin Lindstrom to once again use its Op-Ed space to "publish" non-peer reviewed "science".

Scientists, disgusted struck out at this perversion of science throughout the blogosphere (here, here, here, here though I'm sure I'm missing others). Dozens of prominent cognitive neuroscientists wrote a counter op-ed denouncing this practice (heavily edited by NYT staff).

At work the other day, a graduate student asked me why our field has a lower bar for press shenanigans and wildly implausible claims. I think there are several possible answers to this question (the fact that folk psychology seems to provide causally satisfactory explanations, the allure of pretty pictures of the brain "lighting up", or the intrinsic interest people take in their own brains all come to mind easily. However, I'm afraid that there's also a capitalist component to this one as well: Lindstrom makes his money convincing companies that his "science" will lead to better marketing outcomes. I can't think of a single case where someone impersonates a particle physicist or an inorganic chemist to sell snake oil.

The interest people take in their brains unfortunately creates this market for NeuroNonsense.

The New York Times allowed (nonscientist) Martin Lindstrom to once again use its Op-Ed space to "publish" non-peer reviewed "science".

Scientists, disgusted struck out at this perversion of science throughout the blogosphere (here, here, here, here though I'm sure I'm missing others). Dozens of prominent cognitive neuroscientists wrote a counter op-ed denouncing this practice (heavily edited by NYT staff).

At work the other day, a graduate student asked me why our field has a lower bar for press shenanigans and wildly implausible claims. I think there are several possible answers to this question (the fact that folk psychology seems to provide causally satisfactory explanations, the allure of pretty pictures of the brain "lighting up", or the intrinsic interest people take in their own brains all come to mind easily. However, I'm afraid that there's also a capitalist component to this one as well: Lindstrom makes his money convincing companies that his "science" will lead to better marketing outcomes. I can't think of a single case where someone impersonates a particle physicist or an inorganic chemist to sell snake oil.

The interest people take in their brains unfortunately creates this market for NeuroNonsense.

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

Soundbites, profoundly late

The Economist describes a fascinating new study that shows that people attribute less mind to vegetative patients than to dead persons.

Nature takes on the issue of work-life balance from both sides.

Over at The Atlantic, a nice piece on how deeply held cultural beliefs can kill.

Some hard numbers on prescription drug use for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Jonah Lehrer provacatively asks "is corporate research more reliable than academic research?"

Interesting interview on the future of psychoactive pharmaceuticals.

Nature takes on the issue of work-life balance from both sides.

Over at The Atlantic, a nice piece on how deeply held cultural beliefs can kill.

Some hard numbers on prescription drug use for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Jonah Lehrer provacatively asks "is corporate research more reliable than academic research?"

Interesting interview on the future of psychoactive pharmaceuticals.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Not the new truth serum.

Magnetic Pulses to the Brain Make it Impossible to Lie: Study

Zapping the brain with magnets makes it IMPOSSIBLE to lie, claim scientists

Holy crap! Hold on to your civil liberties...get your tin foil hat.... Something really exciting must be going on in neuroscience.

Right?

So it turns out that these articles refer to the following study:

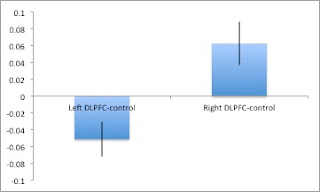

Here, participants were shown red and blue circles and asked to name the color of the circle. At will, the participant could choose to lie or tell the truth about the color of the circle. However, while they were performing this task, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) was applied to one of four brain areas (right or left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), or right or left parietal cortex (PC)). TMS produces a transient magnetic field that produces electrical activity in the brain. As it is causing the brain to have different firing behavior, TMS allows researchers to gain insight into how certain brain areas cause behavior. Previously, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has been implicated in generated lies. Here, the authors sought to assess whether this area has a causal role in deciding whether or not to tell a lie. Here, the parietal cortex served as a control area as it is not generally implicated in the generation of lies.

So, is TMS to DLPFC the new truth serum? Here, I've re-plotted their results:

When TMS was applied to the left DFPFC (compared with the left PC), participants were less likely to choose to tell the truth whereas they were slightly more likely to be truthful when stimulation was applied to the right DLPFC. As you can see from the graph, the effect, although significant, is pretty tiny. The stimulation changes your propensity to lie or truth-tell about 5% in either direction. This cannot be farther from the "impossible to lie" headlines.

Interesting? Yes. Useful for law enforcement? Probably not.

Karton I, & Bachmann T (2011). Effect of prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation on spontaneous truth-telling. Behavioural brain research, 225 (1), 209-14 PMID: 21807030

Zapping the brain with magnets makes it IMPOSSIBLE to lie, claim scientists

Holy crap! Hold on to your civil liberties...get your tin foil hat.... Something really exciting must be going on in neuroscience.

Right?

So it turns out that these articles refer to the following study:

Here, participants were shown red and blue circles and asked to name the color of the circle. At will, the participant could choose to lie or tell the truth about the color of the circle. However, while they were performing this task, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) was applied to one of four brain areas (right or left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), or right or left parietal cortex (PC)). TMS produces a transient magnetic field that produces electrical activity in the brain. As it is causing the brain to have different firing behavior, TMS allows researchers to gain insight into how certain brain areas cause behavior. Previously, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has been implicated in generated lies. Here, the authors sought to assess whether this area has a causal role in deciding whether or not to tell a lie. Here, the parietal cortex served as a control area as it is not generally implicated in the generation of lies.

So, is TMS to DLPFC the new truth serum? Here, I've re-plotted their results:

When TMS was applied to the left DFPFC (compared with the left PC), participants were less likely to choose to tell the truth whereas they were slightly more likely to be truthful when stimulation was applied to the right DLPFC. As you can see from the graph, the effect, although significant, is pretty tiny. The stimulation changes your propensity to lie or truth-tell about 5% in either direction. This cannot be farther from the "impossible to lie" headlines.

Interesting? Yes. Useful for law enforcement? Probably not.

Karton I, & Bachmann T (2011). Effect of prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation on spontaneous truth-telling. Behavioural brain research, 225 (1), 209-14 PMID: 21807030

Saturday, September 3, 2011

Ambien "wakes up" the minimally conscious?

You really must watch this touching video of a man whose minimally conscious state can be alleviated for about an hour a day after taking the sleep drug, Ambien.

Of course, we can't say anything about how this effect might generalize as this is only one patient's experience, but you can see from the video just how amazing of an experience it is!

Of course, we can't say anything about how this effect might generalize as this is only one patient's experience, but you can see from the video just how amazing of an experience it is!

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Sunday soundbites: 8-21

Over at Rationally Speaking, there is a proposal to move towards using odds instead of probabilities when speaking of uncertainty.

I highly recommend this lucid discussion of the brain, free will and criminal responsibility from David Eagleman in The Atlantic.

Running experiments is sometimes a pain, but I'm not sure what to think of this site where one can outsource one's experiments. It's called 'EBay for science', but I worry about how one would trust that the experiments were done well.

What does your writing say about you? Quite a bit, it turns out.

Predictive policing - using statistics to determine the times and locations of future crimes.

I highly recommend this lucid discussion of the brain, free will and criminal responsibility from David Eagleman in The Atlantic.

Running experiments is sometimes a pain, but I'm not sure what to think of this site where one can outsource one's experiments. It's called 'EBay for science', but I worry about how one would trust that the experiments were done well.

What does your writing say about you? Quite a bit, it turns out.

Predictive policing - using statistics to determine the times and locations of future crimes.

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Bayesian truth serum, grading and student evaluations

In one of my last posts, I examined some proposals for making university grading more equitable and less prone to grade inflation. Currently, professors are motivated to inflate grades because high grades correlate with high student evaluations, and these are often the only metrics of teaching effectiveness available. Is there a way to assess professors' teaching abilities independent of the subjective views of students? Similarly, is there a way to get students to provide more objective evaluation responses?

It turns out that one technique may be able to do both. Drazen Prelec, a behavioral economist at MIT, has a very interesting proposal for motivating a person to give truthful opinions in face of knowledge that his opinion is a minority view. In this technique, awesomely named "Bayesian truth serum"*, people give two pieces of information: the first is their honest opinion on the issue at hand, and the second is an estimate of how the respondent thinks other people will answer the first question.

How can this method tell if you are giving a truthful response? The algorithm assigns more points to responses to answers that are "surprisingly common", that is, answers that are more common that collectively predicted. For example, let's say you are being asked about which political candidate you support. A candidate who is chosen (in the first question) by 10% of the respondents, but only predicted as being chosen (the second question) by 5% of the respondents is a surprisingly common answer. This technique gets more true opinions because it is believed that people systematically believe that their own views are unique, and hence will underestimate the degree to which other people will predict their own true views.

But, you might reasonably say, people also believe that they represent reasonable and popular views. They are narcissists and believe that people will tend to believe what they themselves believe. It turns out that this is a corollary to the Bayesian truth serum. Let's say that you are evaluating beer (as I like to do), and let's also say that you're a big fan of Coors (I don't know why you would be, but for the sake of argument....) As a lover of Coors, you believe that most people like Coors, but feel you also recognize that you like Coors more than most people. Therefore, you adjust your actual estimate of Coors' popularity according to this belief, therefore underestimating the popularity of Coors in the population.

It also turns out that this same method can be used to identify experts. It turns out that people who have more meta-knowledge are also the people who provide the most reliable, unbiased ratings. Let's again go back to the beer tasting example. Let's say that there are certain characteristics of beer that might taste very good, but show poor beer brewing technique, say a lot of sweetness. Conversely, there can be some properties of a beer that are normal for a particular process, but seem strange to a novice, such as yeast sediment. An expert will know that too much sweetness is bad and the sediment is fine, and will also know that a novice won't know this. Hence, while the novice will believe that most people agree with his opinion, the expert will accurately predict the novice opinion.

So, what does this all have to do with grades and grade inflation? Glad you asked. Here, I propose two independent uses of BTS to help the grading problem:

1. Student work is evaluated by multiple graders, and the grade the student gets is the "surprisingly common" answer. This motivates graders to be more objective about the piece of work. We can also find the graders who are most expert by sorting them according to meta-knowledge. Of course, this is throwing more resources after grading in an already strained system.

2. When students evaluate the professor, they are also given BTS in an attempt to elicit an objective evaluation.

* When I become a rock star, this will be my band name.

It turns out that one technique may be able to do both. Drazen Prelec, a behavioral economist at MIT, has a very interesting proposal for motivating a person to give truthful opinions in face of knowledge that his opinion is a minority view. In this technique, awesomely named "Bayesian truth serum"*, people give two pieces of information: the first is their honest opinion on the issue at hand, and the second is an estimate of how the respondent thinks other people will answer the first question.

How can this method tell if you are giving a truthful response? The algorithm assigns more points to responses to answers that are "surprisingly common", that is, answers that are more common that collectively predicted. For example, let's say you are being asked about which political candidate you support. A candidate who is chosen (in the first question) by 10% of the respondents, but only predicted as being chosen (the second question) by 5% of the respondents is a surprisingly common answer. This technique gets more true opinions because it is believed that people systematically believe that their own views are unique, and hence will underestimate the degree to which other people will predict their own true views.

But, you might reasonably say, people also believe that they represent reasonable and popular views. They are narcissists and believe that people will tend to believe what they themselves believe. It turns out that this is a corollary to the Bayesian truth serum. Let's say that you are evaluating beer (as I like to do), and let's also say that you're a big fan of Coors (I don't know why you would be, but for the sake of argument....) As a lover of Coors, you believe that most people like Coors, but feel you also recognize that you like Coors more than most people. Therefore, you adjust your actual estimate of Coors' popularity according to this belief, therefore underestimating the popularity of Coors in the population.

It also turns out that this same method can be used to identify experts. It turns out that people who have more meta-knowledge are also the people who provide the most reliable, unbiased ratings. Let's again go back to the beer tasting example. Let's say that there are certain characteristics of beer that might taste very good, but show poor beer brewing technique, say a lot of sweetness. Conversely, there can be some properties of a beer that are normal for a particular process, but seem strange to a novice, such as yeast sediment. An expert will know that too much sweetness is bad and the sediment is fine, and will also know that a novice won't know this. Hence, while the novice will believe that most people agree with his opinion, the expert will accurately predict the novice opinion.

So, what does this all have to do with grades and grade inflation? Glad you asked. Here, I propose two independent uses of BTS to help the grading problem:

1. Student work is evaluated by multiple graders, and the grade the student gets is the "surprisingly common" answer. This motivates graders to be more objective about the piece of work. We can also find the graders who are most expert by sorting them according to meta-knowledge. Of course, this is throwing more resources after grading in an already strained system.

2. When students evaluate the professor, they are also given BTS in an attempt to elicit an objective evaluation.

* When I become a rock star, this will be my band name.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Soundbites!

Mmmmm.... useful math.

It's unfortunately easy to get people to falsely confess to crimes, reviewed in The Economist.

Retractions are up in scientific journals. Now there is a blog devoted to 'em.

Completely awesome matrix of how people on various rungs of the scientific ladder view one another.

Only 4% of the public can name a living scientist. Time for a scientific re-branding.

It's unfortunately easy to get people to falsely confess to crimes, reviewed in The Economist.

Retractions are up in scientific journals. Now there is a blog devoted to 'em.

Completely awesome matrix of how people on various rungs of the scientific ladder view one another.

Only 4% of the public can name a living scientist. Time for a scientific re-branding.

Monday, August 8, 2011

A solution to grade inflation?

In the somewhat limited teaching experience I've had, I have found grading to be particularly difficult. The grade a student receives in my class can determine whether he'll get or keep scholarships and will play a role in determining what kinds of opportunities he'll have after my class. This is a huge responsibility. As a psychophysicist, I worry about my grade-regrade reliability (will I grade the same paper the same way twice), order effects in my grading (if I read a particularly good paper, do all papers after it seem to not measure up?), and whether personal bias is affecting my scoring (Sally is always attentive and asks good questions in class, while Jane, if present, is pugnacious and disruptive).

Of course, the easiest thing is to give everyone generally good grades. The students won't argue that they don't deserve them, and in fact, there is evidence that they'll evaluate me better for it in the end.

And while many institutions have (implicitly or explicitly) adopted this strategy, the problem with grade inflation is that it hurts students who are performing at the top level, and removes accountability from our educational system. So, what do we do about grading?

The Chronicle of Higher Education has an interesting article showing two possible solutions. The second solution involves AI-based grading, which sounds intriguing. Unfortunately, no details were provided for how (or how well) it works, so I remain skeptical. However, the first proposed solution merits some discussion: outsource grading to adjunct professors who are independent of the course, professor and students. The article follows an online university that has enacted this strategy.

Pros of this idea:

- As the grader is not attached to either the professor or the student, bias based on personal feelings towards a student can be eliminated.

- In this instantiation, graders are required to submit detailed justifications for their grades, are provided extensive training and are periodically calibrated for consistency. This can provide far more objective grading than what we do in the traditional classroom.

However, the idea is not perfect. Here are some cons that I see:

- The graders' grades get translated into pass or fail. A pass/fail system does not encourage excellence, original thinking, or going beyond the material given.

- Much of traditional grading is based on improvement and growth over a semester, and this is necessarily absent in this system. Honestly, I only passed the second semester of introductory chemistry in college (after failing the first test) because the professor made an agreement with me that if I improved on subsequent tests, she would drop the first grade.

- Similarly, the relationship between professor and student is made personal through individualized feedback on assignments. Outsourcing grading means that there cannot be a deep, intellectual relationship between parties, which I believe is essential to learning and personal growth.

While not perfect, this is an interesting idea. What are your ideas for improving on it (or grading in general)?

Of course, the easiest thing is to give everyone generally good grades. The students won't argue that they don't deserve them, and in fact, there is evidence that they'll evaluate me better for it in the end.

And while many institutions have (implicitly or explicitly) adopted this strategy, the problem with grade inflation is that it hurts students who are performing at the top level, and removes accountability from our educational system. So, what do we do about grading?

The Chronicle of Higher Education has an interesting article showing two possible solutions. The second solution involves AI-based grading, which sounds intriguing. Unfortunately, no details were provided for how (or how well) it works, so I remain skeptical. However, the first proposed solution merits some discussion: outsource grading to adjunct professors who are independent of the course, professor and students. The article follows an online university that has enacted this strategy.

Pros of this idea:

- As the grader is not attached to either the professor or the student, bias based on personal feelings towards a student can be eliminated.

- In this instantiation, graders are required to submit detailed justifications for their grades, are provided extensive training and are periodically calibrated for consistency. This can provide far more objective grading than what we do in the traditional classroom.

However, the idea is not perfect. Here are some cons that I see:

- The graders' grades get translated into pass or fail. A pass/fail system does not encourage excellence, original thinking, or going beyond the material given.

- Much of traditional grading is based on improvement and growth over a semester, and this is necessarily absent in this system. Honestly, I only passed the second semester of introductory chemistry in college (after failing the first test) because the professor made an agreement with me that if I improved on subsequent tests, she would drop the first grade.

- Similarly, the relationship between professor and student is made personal through individualized feedback on assignments. Outsourcing grading means that there cannot be a deep, intellectual relationship between parties, which I believe is essential to learning and personal growth.

While not perfect, this is an interesting idea. What are your ideas for improving on it (or grading in general)?

Sunday, August 7, 2011

What is it about music?

I can't get enough of this song. I saw Gillian perform this in 2005 or 2006, and I'm so happy that she's finally put it on an album. Why have I played this song over 20 times in one day? Of course, there are technical aspects of it that are neat (I particularly like the frequent dissonances that resolve in Rawlings' guitar line), and the lyrics remind me of the time in my life when I first heard the song, but are these alone enough to produce such strong emotional reactions? Why does music give us chills? Why does it freak us out?

Indeed, music seems to activate the neural reward system, and certainly there are no lack of hand-wavy evolutionary psychology theories on music's emotional pull. But why does music make us feel things?

We have several touch/feeling metaphors for music: a person's voice can be "rough" or "velvet", musical passages may be "light" or "heavy, and pitches can be "rising" or "falling". Given this mapping, can we find cross-modal effects of music and feeling? One type of cross-modal effect is synaesthesia, where two senses are correlated in the same person. To a synaesthete, letters can have color, tastes can have shape, etc. The most common form of synaesthesia related to music is "colored music". Can we find evidence for "touched music"?

This paper is the reason I would love to be a psychologist in the 1950s. Here, the goal was to see which combinations of senses could be combined in synaesthesia, either in naturally occurring synaesthesia or in (I can't make this up) mescaline-induced synaesthesia. Here is the summary matrix of their results:

(An "N" in a cell represents a naturally occurring synaesthesia, and an "E" in a cell represents an "experimentally induced" synaestesia through mescaline).

So, who were the participants in this study?? The two authors and their two friends, one of whom was a natural music-tactile synaesthete. (See, I told you psychology was fun in the 1950s!)

This synaesthete described her experiences: "A trumpet sound is the feel of some sort of plastics; like touching certain sorts of stiffish plastic cloth - smooth and shiny - I felt it slipping." Sounds interesting, but does not sound like the "chilling", emotional experience.

It turns out that musical chills, while having a strong physiological basis, are not automatic but rather require attention. This implies that music and somatosensory (touch) systems are not necessarily linked.

So, no real answers in this post, but there's one other cool piece of data that I'll throw into the mix. So, if you ask people to assign colors to both emotions and music, people (normal, non-synaesthetes) are ridiculously similar in the colors chosen. Of course, this was presented at a conference and is not in final, peer-reviewed form, but it is certainly interesting.

Indeed, music seems to activate the neural reward system, and certainly there are no lack of hand-wavy evolutionary psychology theories on music's emotional pull. But why does music make us feel things?

We have several touch/feeling metaphors for music: a person's voice can be "rough" or "velvet", musical passages may be "light" or "heavy, and pitches can be "rising" or "falling". Given this mapping, can we find cross-modal effects of music and feeling? One type of cross-modal effect is synaesthesia, where two senses are correlated in the same person. To a synaesthete, letters can have color, tastes can have shape, etc. The most common form of synaesthesia related to music is "colored music". Can we find evidence for "touched music"?

This paper is the reason I would love to be a psychologist in the 1950s. Here, the goal was to see which combinations of senses could be combined in synaesthesia, either in naturally occurring synaesthesia or in (I can't make this up) mescaline-induced synaesthesia. Here is the summary matrix of their results:

(An "N" in a cell represents a naturally occurring synaesthesia, and an "E" in a cell represents an "experimentally induced" synaestesia through mescaline).

So, who were the participants in this study?? The two authors and their two friends, one of whom was a natural music-tactile synaesthete. (See, I told you psychology was fun in the 1950s!)

This synaesthete described her experiences: "A trumpet sound is the feel of some sort of plastics; like touching certain sorts of stiffish plastic cloth - smooth and shiny - I felt it slipping." Sounds interesting, but does not sound like the "chilling", emotional experience.

It turns out that musical chills, while having a strong physiological basis, are not automatic but rather require attention. This implies that music and somatosensory (touch) systems are not necessarily linked.

So, no real answers in this post, but there's one other cool piece of data that I'll throw into the mix. So, if you ask people to assign colors to both emotions and music, people (normal, non-synaesthetes) are ridiculously similar in the colors chosen. Of course, this was presented at a conference and is not in final, peer-reviewed form, but it is certainly interesting.

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Saturday soundbites: 6 RBI edition

Is Google the closest thing we have to mind reading?

Mind Hacks points to a great article on blind mathematicians. It turns out that they tend to be talented in geometry.

This week in neuro-nonsense, dieting causes your brain to eat itself.

Neuroskeptic describes a cool new proposed antidepressant that selectively modifies gene expression.

Google and Microsoft are launching new biobliometric tools, according to Nature.

Over at the Frontal Cortex, Jonah Lehrer reviews a study telling us that the Flynn effect is about more than just bringing up the lower part of the IQ distribution through nutrition, de-leading, etc. The top 5% are also getting smarter.

How getting tenure actually does change your life.

Can we predict which soldiers are going to develop PTSD? Should we?

Mind Hacks points to a great article on blind mathematicians. It turns out that they tend to be talented in geometry.

This week in neuro-nonsense, dieting causes your brain to eat itself.

Neuroskeptic describes a cool new proposed antidepressant that selectively modifies gene expression.

Google and Microsoft are launching new biobliometric tools, according to Nature.

Over at the Frontal Cortex, Jonah Lehrer reviews a study telling us that the Flynn effect is about more than just bringing up the lower part of the IQ distribution through nutrition, de-leading, etc. The top 5% are also getting smarter.

How getting tenure actually does change your life.

Can we predict which soldiers are going to develop PTSD? Should we?

Friday, August 5, 2011

Proposed changes to IRBs

Institutional review boards (IRBs) are committees formed within universities and research organizations. Their job is to review proposed research that uses human subjects, evaluating it for ethical treatment of the human participants. It's an important job given the rather spotty history we have with ethical research (see here, here and here among others).

However, there is a wide range of activities that count as human subjects research, ranging from experimental vaccine trials to personality tests, from political opinions to tests of color vision. Currently, all of this research is broken up into two groups: "regular" human subjects research, which is subject to a full review process and "minimal risk" research, which is subject to a faster review process. Research is defined as minimal risk when it poses no more potential for physical or psychological harm than any other activity in daily life.

My research falls into the minimal risk category. My experiments have been described by several subjects as being "like the world's most boring video game". Outside of being boring, they are not physically harmful, and there is no exposure of deep psychological secrets either. No matter. Each year, researchers like me fill out extensive protocols detailing the types of experiments they propose to do, detailing all possible risks, outlining how subject confidentiality will be maintained, etc. And each participant in a study (each time s/he participates) receives a 3-4 page legal document explaining all of the risks and benefits of the research, which the subject signs to give his consent.

This does seem to be overkill for research which really doesn't pose any sort of physical or psychological threat to participants, and I applaud new efforts to modernize and streamline this process. (Read here for a great summary of the details. Researchers: you can comment until the end of September, the Department of Health and Human Services is soliciting opinions on a bunch of things).

Among the changes are moving minimal risk research from expedited review to no review, and eliminating the need for physical consent forms (a verbal "is this OK with you?" will suffice). These are both good things that would improve my life substantially. However, I believe that standardizing IRB policies across the country would do the most good.

I am currently at my 4th institution and have seen as many IRBs. Two of them have been entirely reasonable, requiring the minimal amount of paperwork and approving minimal risk research across the board. The other two, however, have been less helpful. As Tal Yarkoni points out, "IRB analysts have an incentive to be pedantic (since they rarely lose their jobs if they ask for too much detail, but could be liable if they give too much leeway and something bad happens)". However, I think it goes beyond this. In some sense, IRBs feel they are productive by showing that they have stopped or delayed some proportion of the research that crosses their desks.

I have had an IRB reject my protocol because they didn't like my margin size, didn't like my font size, and didn't like the cute cartoon I put on my recruitment posters (apparently cartoons are coercive). I've had an IRB send an electrician into the lab with a volt meter to make sure my computer monitor wouldn't electrocute anyone. My last institution did not approve an experiment that was a cornerstone of my fellowship proposal as it required data to be gathered online (this is very common in my field) and I couldn't guarantee that someone outside of my approved age range (18-50) was doing my experiment. Under the current rules, I couldn't just use my collaborator's IRB approval as all institutions need to approve a protocol. However, another of the proposed changes will require only one approval.

I'm very optimistic about these proposed changes... let's hope they happen!

However, there is a wide range of activities that count as human subjects research, ranging from experimental vaccine trials to personality tests, from political opinions to tests of color vision. Currently, all of this research is broken up into two groups: "regular" human subjects research, which is subject to a full review process and "minimal risk" research, which is subject to a faster review process. Research is defined as minimal risk when it poses no more potential for physical or psychological harm than any other activity in daily life.

My research falls into the minimal risk category. My experiments have been described by several subjects as being "like the world's most boring video game". Outside of being boring, they are not physically harmful, and there is no exposure of deep psychological secrets either. No matter. Each year, researchers like me fill out extensive protocols detailing the types of experiments they propose to do, detailing all possible risks, outlining how subject confidentiality will be maintained, etc. And each participant in a study (each time s/he participates) receives a 3-4 page legal document explaining all of the risks and benefits of the research, which the subject signs to give his consent.

This does seem to be overkill for research which really doesn't pose any sort of physical or psychological threat to participants, and I applaud new efforts to modernize and streamline this process. (Read here for a great summary of the details. Researchers: you can comment until the end of September, the Department of Health and Human Services is soliciting opinions on a bunch of things).

Among the changes are moving minimal risk research from expedited review to no review, and eliminating the need for physical consent forms (a verbal "is this OK with you?" will suffice). These are both good things that would improve my life substantially. However, I believe that standardizing IRB policies across the country would do the most good.

I am currently at my 4th institution and have seen as many IRBs. Two of them have been entirely reasonable, requiring the minimal amount of paperwork and approving minimal risk research across the board. The other two, however, have been less helpful. As Tal Yarkoni points out, "IRB analysts have an incentive to be pedantic (since they rarely lose their jobs if they ask for too much detail, but could be liable if they give too much leeway and something bad happens)". However, I think it goes beyond this. In some sense, IRBs feel they are productive by showing that they have stopped or delayed some proportion of the research that crosses their desks.

I have had an IRB reject my protocol because they didn't like my margin size, didn't like my font size, and didn't like the cute cartoon I put on my recruitment posters (apparently cartoons are coercive). I've had an IRB send an electrician into the lab with a volt meter to make sure my computer monitor wouldn't electrocute anyone. My last institution did not approve an experiment that was a cornerstone of my fellowship proposal as it required data to be gathered online (this is very common in my field) and I couldn't guarantee that someone outside of my approved age range (18-50) was doing my experiment. Under the current rules, I couldn't just use my collaborator's IRB approval as all institutions need to approve a protocol. However, another of the proposed changes will require only one approval.

I'm very optimistic about these proposed changes... let's hope they happen!

Thursday, August 4, 2011

Fun graphics

Hasn't it been a long week? Instead of serious science, how about some pretty pictures?

We must all be getting way smarter than even the Flynn effect would predict - check out grade inflation at universities over the last 90 years.

Yes, this is really how science is done.

We must all be getting way smarter than even the Flynn effect would predict - check out grade inflation at universities over the last 90 years.

Yes, this is really how science is done.

Sunday, July 24, 2011

Soundbites: relocation blues edition

The ever-informative Andrew Gelman asks how we statistically evaluate some of the rather improbable claims from recent studies.

Speaking of improbable claims, Ed Yong deconstructs the latest on Google ruining your mind.

Peter Kramer defends antidepressants in the New York Times.

Neuroethics at the Core has a nice discussion of the issues involved in pharmacologically enhancing soldiers.

The New York Times education section has a special issue on grad school for all of your bitter academic ranting. I especially like these infographics.

Speaking of improbable claims, Ed Yong deconstructs the latest on Google ruining your mind.

Peter Kramer defends antidepressants in the New York Times.

Neuroethics at the Core has a nice discussion of the issues involved in pharmacologically enhancing soldiers.

The New York Times education section has a special issue on grad school for all of your bitter academic ranting. I especially like these infographics.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Managing scholarly reading

Reading, after a certain age, diverts the mind too much from its creative pursuits. Any man who reads too much and uses his own brain too little falls into lazy habits of thinking. —ALBERT EINSTEIN

How much literature should one read as an academic? Of course, the answer will vary by field, but even within my own field, I find little consensus as to the "right" amount of reading to do.

It is true that no one can read everything that is published, even in a single field such as cognitive science, while maintaining one's own productivity. In my Google reader, I subscribe to the RSS of 26 journals, and from these, I get an average of 37 articles per day. However, in an average day, I feel like I should pay attention to 5 of these. If I were to closely read all of these, I would run out of time to create new experiments, analyze data and write my own papers.

It turns out that in an average day, I'll read one of these papers and "tag" the other 4 as things I should read. But this strategy gets out of control quickly. In May, I went to a conference, didn't check my reader for a couple of days and came back to over 500 journal articles, or around 35 that I felt deserved to be read. I have over 1300 items tagged "to read" in my Zotero library. At my current rate of reading, it would take me over 3.5 years to get through the backlog even if I didn't add a single article to the queue.

So, how to stay informed in an age of information overload? It seems that there are a few strategies:

1. Read for, rather than read to. In other words, read when knowledge on a particular topic is to be used in a paper or grant review, but don't read anything without a specific purpose for that information. According to proponents of this method, information obtained when reading-for-reading's-take will be lost anyway, leading to re-reading when one needs the information.

This method vastly decreases the overwhelming nature of the information, and makes info acquisition efficient. However, it is not always practical for science: if you're only reading for your own productivity, you're going to miss critical papers, and at worst, are going to be doing experiments that were already done.

2. Social "reading", augmented by abstract skimming. In this method, one does not spend time reading, but spends time going to as many talks and conferences as possible, learning about literature by using the knowledge of one's colleagues. This method seems to work best in crowded fields. The more unique your research program, the more you'll have to do your own reading. And all of this traveling is time and money consuming.

3. Don't worry about checking through many journals, but set alerts for the specific topics. My favorite is PubCrawler, suggested by Neuroskeptic. Works well when my key words and the authors' key words coincide, but I seem to have set too many topics and I get both too many "misses" and "false alarms".

How do you keep up with literature?

How much literature should one read as an academic? Of course, the answer will vary by field, but even within my own field, I find little consensus as to the "right" amount of reading to do.

It is true that no one can read everything that is published, even in a single field such as cognitive science, while maintaining one's own productivity. In my Google reader, I subscribe to the RSS of 26 journals, and from these, I get an average of 37 articles per day. However, in an average day, I feel like I should pay attention to 5 of these. If I were to closely read all of these, I would run out of time to create new experiments, analyze data and write my own papers.

It turns out that in an average day, I'll read one of these papers and "tag" the other 4 as things I should read. But this strategy gets out of control quickly. In May, I went to a conference, didn't check my reader for a couple of days and came back to over 500 journal articles, or around 35 that I felt deserved to be read. I have over 1300 items tagged "to read" in my Zotero library. At my current rate of reading, it would take me over 3.5 years to get through the backlog even if I didn't add a single article to the queue.

So, how to stay informed in an age of information overload? It seems that there are a few strategies:

1. Read for, rather than read to. In other words, read when knowledge on a particular topic is to be used in a paper or grant review, but don't read anything without a specific purpose for that information. According to proponents of this method, information obtained when reading-for-reading's-take will be lost anyway, leading to re-reading when one needs the information.

This method vastly decreases the overwhelming nature of the information, and makes info acquisition efficient. However, it is not always practical for science: if you're only reading for your own productivity, you're going to miss critical papers, and at worst, are going to be doing experiments that were already done.

2. Social "reading", augmented by abstract skimming. In this method, one does not spend time reading, but spends time going to as many talks and conferences as possible, learning about literature by using the knowledge of one's colleagues. This method seems to work best in crowded fields. The more unique your research program, the more you'll have to do your own reading. And all of this traveling is time and money consuming.

3. Don't worry about checking through many journals, but set alerts for the specific topics. My favorite is PubCrawler, suggested by Neuroskeptic. Works well when my key words and the authors' key words coincide, but I seem to have set too many topics and I get both too many "misses" and "false alarms".

How do you keep up with literature?

Saturday, July 9, 2011

Bitter academic roundup

So, you think you want to go to graduate school? You might want to consider the following:

This infographic nicely details many of the perils of the PhD and post-PhD process.

Here's what an honest graduate school ad might look like.

This infographic nicely details many of the perils of the PhD and post-PhD process.

Here's what an honest graduate school ad might look like.

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Is college worth it for everyone?

In yesterday's New York Times, David Leonhardt opined that we ought to send as many young adults to college as possible. His economic arguments ran as follows:

- The income delta between college grads and non-college grads has increased from 40% to over 80% in the last three decades.

- If one calculates a return on investment for a college education, it is 15%, higher than stocks, and certainly higher than current real-estate.

Unfortunately, he completely glosses over the problem of cost. He writes:

- The income delta between college grads and non-college grads has increased from 40% to over 80% in the last three decades.

- If one calculates a return on investment for a college education, it is 15%, higher than stocks, and certainly higher than current real-estate.

Unfortunately, he completely glosses over the problem of cost. He writes:

"First, many colleges are not very expensive, once financial aid is taken into account. Average net tuition and fees at public four-year colleges this past year were only about $2,000 (though Congress may soon cut federal financial aid)."

As if the eminent cutting of federal financial aid can be reduced to a parenthetical! The reality is that college prices have increased over 130% since 1988 while median family incomes have remained stagnant. This situation makes college possible only through the amassing of large amounts of student debt. Indeed, for the first time in this country, student loan debt has surpassed credit card debt. Taking on this kind of debt in this lackluster economy is problematic. Furthermore unlike mortgages, student loan debt does not go away with bankruptcy, loading some thinkers to forecast education as the next bubble.

Leonhardt also unhelpfully compares the arguments against universal college education to the arguments against universal high school education from over half a century ago. This would be fine if we were in the position to make four years of university education part of public education. However, calling for all families to take on this debt seems irresponsible and elitist.

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

Soundbites: misplaced adrenaline edition

New vaccine-autism paper expertly dismembered by Neuroskeptic.

Plastic surgery to prevent recidivism?

Colleges are not as meritocratic as they would lead us to believe.

Neurophilosophy on human echolocation in the blind.

During the Singularity, will there be corporate sponsors for your thoughts? Asked by Sue Halpern for the New York Review of Books.

Brain Ethics argues that "neuromarketing", when not used for marketing, might be a good thing.

Review of David Eagleman's new book at Nature.

I highly recommend this New York Times article on the consciousness of conjoined twins.

Scientific American interviews Chris Chabris on how to test the "10,000 hours" idea.

On a light ending, I can't tell whether this is the coolest or weirdest thing ever.

Plastic surgery to prevent recidivism?

Colleges are not as meritocratic as they would lead us to believe.

Neurophilosophy on human echolocation in the blind.

During the Singularity, will there be corporate sponsors for your thoughts? Asked by Sue Halpern for the New York Review of Books.

Brain Ethics argues that "neuromarketing", when not used for marketing, might be a good thing.

Review of David Eagleman's new book at Nature.

I highly recommend this New York Times article on the consciousness of conjoined twins.

Scientific American interviews Chris Chabris on how to test the "10,000 hours" idea.

On a light ending, I can't tell whether this is the coolest or weirdest thing ever.

Thursday, June 9, 2011

Edison, Gretsky and the gritty side of success

"If I find 10,000 ways something won’t work, I haven’t failed. I am not discouraged, because every wrong attempt discarded is another step forward." Thomas Edison.

Fundamentally different views of achievement can be seen in the well-known debates between Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison. Tesla, the theoretician, conducted experiments only after careful consideration and calculation while Edison's approach was an "empirical dragnet" according to Tesla.

Similarly, hockey great Wayne Gretsky has stated "You miss 100% of the shots you don't take".

Is the key to success to multiply your rate of failure?

Of course, ability matters. But how much does perseverance matter? In other words, how much difference in success will be seen for two people of equal ability but unequal perseverance?

In success psychology, one can measure "grit", defined as "perseverance and passion for long-term goals". Duckworth and colleagues have created a self-report measure for this trait, known as the Grit Scale. In this survey, items such as "I have achieved a goal that took years of work" correlate with high grit, while items such as "New ideas and new projects sometimes distract me from previous ones" are negatively correlated with grit.

Here are some interesting things they found about grit:

* Highly educated people have more grit than people with less education.

* When controlling for age, grit increases with age.

* Grit is related to the Big Five Personality trait of Conscientiousness.

* When examining undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania, students with more grit had a higher GPA, but students with lower SAT scores had higher grit. This could suggest that getting to an elite university can be through ability (reflected in SAT scores) or grit.

* Although grit was unrelated to rankings of West Point cadets, grit was the best predictor of whether cadets would complete summer training.

* Students with higher grit were more likely to make it to the final round of the National Spelling Bee, due to putting in more time to studying.

I've been thinking a lot about grit in the last day of trying to win a scholarship (as I wrote about yesterday). The video I made is about grit, but the promotion I'm doing for it is putting me way out of my comfort zone as a shy person. I may fail, but I'll be back. :)

Fundamentally different views of achievement can be seen in the well-known debates between Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison. Tesla, the theoretician, conducted experiments only after careful consideration and calculation while Edison's approach was an "empirical dragnet" according to Tesla.

Similarly, hockey great Wayne Gretsky has stated "You miss 100% of the shots you don't take".

Is the key to success to multiply your rate of failure?

Of course, ability matters. But how much does perseverance matter? In other words, how much difference in success will be seen for two people of equal ability but unequal perseverance?

In success psychology, one can measure "grit", defined as "perseverance and passion for long-term goals". Duckworth and colleagues have created a self-report measure for this trait, known as the Grit Scale. In this survey, items such as "I have achieved a goal that took years of work" correlate with high grit, while items such as "New ideas and new projects sometimes distract me from previous ones" are negatively correlated with grit.

Here are some interesting things they found about grit:

* Highly educated people have more grit than people with less education.

* When controlling for age, grit increases with age.

* Grit is related to the Big Five Personality trait of Conscientiousness.

* When examining undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania, students with more grit had a higher GPA, but students with lower SAT scores had higher grit. This could suggest that getting to an elite university can be through ability (reflected in SAT scores) or grit.

* Although grit was unrelated to rankings of West Point cadets, grit was the best predictor of whether cadets would complete summer training.

* Students with higher grit were more likely to make it to the final round of the National Spelling Bee, due to putting in more time to studying.

I've been thinking a lot about grit in the last day of trying to win a scholarship (as I wrote about yesterday). The video I made is about grit, but the promotion I'm doing for it is putting me way out of my comfort zone as a shy person. I may fail, but I'll be back. :)

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

Soundbites: leaving New England edition

Neuroskeptic thinks he can fix science.... and I believe him.

The age at which scientists make important discoveries has been increasing.

Blue light for cognitive enhancement?

I did WHAT in my sleep??? The ethical complications of sleep disorders from Bering in Mind.

Campaign for the Future of Higher Education.

The age at which scientists make important discoveries has been increasing.

Blue light for cognitive enhancement?

I did WHAT in my sleep??? The ethical complications of sleep disorders from Bering in Mind.

Campaign for the Future of Higher Education.

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

A reverse decline effect for RSVP?

Last week I attended the Vision Sciences Society annual meeting in Florida. Good times, good science. Although I don't use this blog for talking about my own research or field, I was struck by a talk from Molly Potter that was germane to this blog. (In full disclosure, Molly was the chair of my PhD committee, a personal hero of mine, and a large influence on my thinking).

In the 1960s and 1970s, Prof. Potter sought to study the temporal limits of complex visual processing. As our eyes move multiple times per second, the visual input we receive is constantly changing. To emulate this process, she developed the technique of rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP). In this method, one presents a participant with a stream of photographs, one after another, for a very brief time (half a second or less per picture). She found that when you give a participant a target scene (either by showing the picture or describing the picture), the participant can detect the presence or absence of this picture even when the pictures are presented for a tenth of a second each! Below is an example of one of these displays. Try to find a picture of the Dalai Lama wearing a cowboy hat.

Pretty cool, huh?

In her new research, Prof. Potter was trying to determine how much faster the visual system can be pushed by presenting RSVP steams that were only 50, 33 or even 13ms per picture. Here is a graph adapted from my notes at her talk:

Even at 13 ms per image, participants were performing at about 60% correct, and by 80ms per image, they were nearly perfect.

"Huh" I thought to myself during the talk, "this is really high performance. It seems even higher than performances for longer presentation times that were in the original papers".

So back in Boston, I looked up the original findings. Here is one of the graphs from 1975:

So, participants in 1975 needed 125ms per picture to reach the same level or performance that modern participants can perform with 33ms/picture.

I've complained a bit here about the so-called "decline effect", the phenomenon of effect sizes in research declining over time. The increased performance for RSVP displays can be seen as a kind of reverse decline effect.

Why?

In 1975, the only way to present pictures at a rapid rate was through the use of a tachistoscope. Today's research is done on computer monitors. Although the temporal properties of CRT monitors are well-worked out, perhaps these two methods are not fully equivalent. On the other hand, compared to 1975, our lives are full of fast movie-cuts, video games and other rapid stimuli, and so the new generation of participants may have faster visual systems.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Prof. Potter sought to study the temporal limits of complex visual processing. As our eyes move multiple times per second, the visual input we receive is constantly changing. To emulate this process, she developed the technique of rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP). In this method, one presents a participant with a stream of photographs, one after another, for a very brief time (half a second or less per picture). She found that when you give a participant a target scene (either by showing the picture or describing the picture), the participant can detect the presence or absence of this picture even when the pictures are presented for a tenth of a second each! Below is an example of one of these displays. Try to find a picture of the Dalai Lama wearing a cowboy hat.

Pretty cool, huh?

In her new research, Prof. Potter was trying to determine how much faster the visual system can be pushed by presenting RSVP steams that were only 50, 33 or even 13ms per picture. Here is a graph adapted from my notes at her talk:

Even at 13 ms per image, participants were performing at about 60% correct, and by 80ms per image, they were nearly perfect.

"Huh" I thought to myself during the talk, "this is really high performance. It seems even higher than performances for longer presentation times that were in the original papers".

So back in Boston, I looked up the original findings. Here is one of the graphs from 1975:

So, participants in 1975 needed 125ms per picture to reach the same level or performance that modern participants can perform with 33ms/picture.

I've complained a bit here about the so-called "decline effect", the phenomenon of effect sizes in research declining over time. The increased performance for RSVP displays can be seen as a kind of reverse decline effect.

Why?

In 1975, the only way to present pictures at a rapid rate was through the use of a tachistoscope. Today's research is done on computer monitors. Although the temporal properties of CRT monitors are well-worked out, perhaps these two methods are not fully equivalent. On the other hand, compared to 1975, our lives are full of fast movie-cuts, video games and other rapid stimuli, and so the new generation of participants may have faster visual systems.

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Growing PhDs "like mushrooms"

If you have been following this blog, it comes as no surprise that I frequently worry about the state of the university system. I believe there are structural problems in the system that are a disservice to students (both at the undergraduate and graduate levels) as well as staff (particularly adjuncts and non-tenure track faculty, but also to junior tenure-track professors as well).

Recently, Nature published a series of opinion articles on the over-production of PhDs in the sciences. We are producing too many people who are apprenticed in a career path that can accommodate only a fraction of them.

As a result, we are spending longer in graduate school and in our postdocs, but the number of people passing through the needle eye to professorship is shrinking as tenure-track jobs get replaced with temporary and adjunct positions. In 1973, 55% of US biology PhDs secured tenure-track positions within six years of completing their degrees, and only 2% were in a postdoc or other untenured academic position. By 2006, only 15% were in tenured positions six years after graduating, with 18% un-tenured. This largely fits with my perception: it has been seven years since I began graduate school, and considering my incoming class, we are evenly spread across remaining in school, having a post-doc and getting a job in industry. Not one of us currently has a tenure-track faculty position. Something must be very broken in the system for prospects to be this bleak for graduates of a top-five department.

So why doesn't the market change such that supply meets demand? Essentially, it's that the system runs on cheap graduate and postdoctoral labor. "Yet many academics are reluctant to rock the boat as long as they are rewarded with grants (which pay for cheap PhD students) and publications (produced by their cheap PhD students). So are universities, which often receive government subsidies to fill their PhD spots." In fact, faculty members who are reluctant to perpetuate this cycle are punished in grant review, writing in costs for a research scientist at $80,000 per year when others have the same work done by a postdoc at $40,000 per year.

So, how did we get here? Part of the issue has to be that more people are going to college than ever before and the university system does not properly scale to the demand. In the US in 1970, only 11% of people over the age of 25 had a bachelor's degree, but this number had climbed to 28% by 2009. So more graduate students, postdocs and adjuncts are being used to teach the courses to accommodate all of these new students. While some claim that it is just too expensive to have tenure-track faculty teaching all of these courses, one must also consider the recent trend towards massive salaries for university professors.

Actually, if anyone could explain university economics to me, I'd be grateful.

And where do we go from here? Personally, I love the suggestions made by William Deresiewicz in this fantastic article. Particularly, "The answer is to hire more professors: real ones, not academic lettuce-pickers."

Recently, Nature published a series of opinion articles on the over-production of PhDs in the sciences. We are producing too many people who are apprenticed in a career path that can accommodate only a fraction of them.

As a result, we are spending longer in graduate school and in our postdocs, but the number of people passing through the needle eye to professorship is shrinking as tenure-track jobs get replaced with temporary and adjunct positions. In 1973, 55% of US biology PhDs secured tenure-track positions within six years of completing their degrees, and only 2% were in a postdoc or other untenured academic position. By 2006, only 15% were in tenured positions six years after graduating, with 18% un-tenured. This largely fits with my perception: it has been seven years since I began graduate school, and considering my incoming class, we are evenly spread across remaining in school, having a post-doc and getting a job in industry. Not one of us currently has a tenure-track faculty position. Something must be very broken in the system for prospects to be this bleak for graduates of a top-five department.

So why doesn't the market change such that supply meets demand? Essentially, it's that the system runs on cheap graduate and postdoctoral labor. "Yet many academics are reluctant to rock the boat as long as they are rewarded with grants (which pay for cheap PhD students) and publications (produced by their cheap PhD students). So are universities, which often receive government subsidies to fill their PhD spots." In fact, faculty members who are reluctant to perpetuate this cycle are punished in grant review, writing in costs for a research scientist at $80,000 per year when others have the same work done by a postdoc at $40,000 per year.

So, how did we get here? Part of the issue has to be that more people are going to college than ever before and the university system does not properly scale to the demand. In the US in 1970, only 11% of people over the age of 25 had a bachelor's degree, but this number had climbed to 28% by 2009. So more graduate students, postdocs and adjuncts are being used to teach the courses to accommodate all of these new students. While some claim that it is just too expensive to have tenure-track faculty teaching all of these courses, one must also consider the recent trend towards massive salaries for university professors.

Actually, if anyone could explain university economics to me, I'd be grateful.

And where do we go from here? Personally, I love the suggestions made by William Deresiewicz in this fantastic article. Particularly, "The answer is to hire more professors: real ones, not academic lettuce-pickers."

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

(Just) soundbites