Magnetic Pulses to the Brain Make it Impossible to Lie: Study

Zapping the brain with magnets makes it IMPOSSIBLE to lie, claim scientists

Holy crap! Hold on to your civil liberties...get your tin foil hat.... Something really exciting must be going on in neuroscience.

Right?

So it turns out that these articles refer to the following study:

Here, participants were shown red and blue circles and asked to name the color of the circle. At will, the participant could choose to lie or tell the truth about the color of the circle. However, while they were performing this task, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) was applied to one of four brain areas (right or left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), or right or left parietal cortex (PC)). TMS produces a transient magnetic field that produces electrical activity in the brain. As it is causing the brain to have different firing behavior, TMS allows researchers to gain insight into how certain brain areas cause behavior. Previously, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has been implicated in generated lies. Here, the authors sought to assess whether this area has a causal role in deciding whether or not to tell a lie. Here, the parietal cortex served as a control area as it is not generally implicated in the generation of lies.

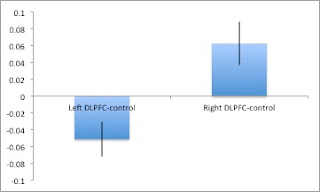

So, is TMS to DLPFC the new truth serum? Here, I've re-plotted their results:

When TMS was applied to the left DFPFC (compared with the left PC), participants were less likely to choose to tell the truth whereas they were slightly more likely to be truthful when stimulation was applied to the right DLPFC. As you can see from the graph, the effect, although significant, is pretty tiny. The stimulation changes your propensity to lie or truth-tell about 5% in either direction. This cannot be farther from the "impossible to lie" headlines.

Interesting? Yes. Useful for law enforcement? Probably not.

Karton I, & Bachmann T (2011). Effect of prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation on spontaneous truth-telling. Behavioural brain research, 225 (1), 209-14 PMID: 21807030

Showing posts with label choice. Show all posts

Showing posts with label choice. Show all posts

Monday, September 26, 2011

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

Gender and scientific success

I didn't want to write this post. I really don't want to touch this with a ten foot pole. What follows is messy and complicated and guaranteed to make everyone mad at least some of the time. (Ask Larry Summers).

We need a sane approach to how we deal with gender in the sciences.

Women are making measurable representation gains in the sciences. This is an undisputed good. Everyone benefits when the right people are doing the right job. However, despite the fact that the majority of bachelor's degrees are now being awarded to women, women only make up about 20% of professorships in math and the sciences. Why?

The three basic alternative answers: 1.) women tend not to choose careers in math or science (either willingly or due to life/family circumstances); 2.) women are barred from achievement in math and science through acts of willful discrimination; or 3.) women do not have the same aptitude for achievement in math and sciences as men.

This is a difficult issue to study as people's careers cannot be manipulated experimentally, and we are left to mostly correlational evidence. An exception are CV studies where identical CVs are given to judges with either a woman or man's name on the top. Judges are asked to determine the competence of the candidates. These studies typically find that the "male candidates" are judged to be more competent than the "female candidates". As no objective differences exist between them, this is a measure of sex discrimination.

Reviewing the correlational evidence for gender discrimination in the sciences, Ceci and Williams find that when examining researchers with equal access to resources (lab space, teaching loads, etc), that no productivity difference is found between male and female scientists. Female scientists are, on average, less likely to have as many resources as male scientists as they are more likely to take positions with heavier teaching loads. How to reconcile the CV studies showing discrimination and the correlational evidence suggesting none? In an excellent analysis of the Ceci and Williams paper, Alison Gopnik asserts a possible hypothesis: "Women, knowing that they are subject to discrimination, may work twice as hard to produce high-quality grants and papers, so that the high quality offsets the influence of discrimination".

It's possible. But Gopnik also admits that it is also possible that policy changes could be responsible. In other words, that affirmative action-style policies that give women advantages could counteract the subconscious gender discrimination seen in the CV studies.

There's a darker side to these policies, though. Some worry about the discounting of a female professor's abilities, assuming she rose to the position via policy rather than talent. Furthermore, some policies designed to given women more voice actually end up give them more work - if a certain number of women need to be on a committee, then female professors are doing more service work than their male counterparts.

And then there's the matter of why female faculty find themselves in low-resource situations to begin with. Stated eloquently by Gopnik, "the conflict between female fertility and the typical tenure process is one important factor in women's access to resources. You could say that universities don't discriminate against women, they just discriminate against people whose fertility declines rapidly after 35."

And well-meaning policies also interact with the fertility issue in insidious ways. For example, many universities offer to "pause" the tenure clock for a year for a faculty member who gives birth before tenure. Sounds great, right? It could be, except that there is a tremendous amount of pressure to not take this credit for fear of seeming weak. This is especially true in departments that have faculty members who have already chosen not to take the time.

So... we have unconscious discrimination, conscious policies to counter said unconscious discrimination, conscious and unconscious backlash against the policies, and a structural problem for female fertility. In other words, it's a complicated picture and I don't know what the answer is. I do, however agree with Shankar Vedantam's assessment: "It is true that fewer women than men break into science and engineering careers today because they do not choose such careers. What isn't true is that those choices are truly "free.""

We need a sane approach to how we deal with gender in the sciences.

Women are making measurable representation gains in the sciences. This is an undisputed good. Everyone benefits when the right people are doing the right job. However, despite the fact that the majority of bachelor's degrees are now being awarded to women, women only make up about 20% of professorships in math and the sciences. Why?

The three basic alternative answers: 1.) women tend not to choose careers in math or science (either willingly or due to life/family circumstances); 2.) women are barred from achievement in math and science through acts of willful discrimination; or 3.) women do not have the same aptitude for achievement in math and sciences as men.

This is a difficult issue to study as people's careers cannot be manipulated experimentally, and we are left to mostly correlational evidence. An exception are CV studies where identical CVs are given to judges with either a woman or man's name on the top. Judges are asked to determine the competence of the candidates. These studies typically find that the "male candidates" are judged to be more competent than the "female candidates". As no objective differences exist between them, this is a measure of sex discrimination.

Reviewing the correlational evidence for gender discrimination in the sciences, Ceci and Williams find that when examining researchers with equal access to resources (lab space, teaching loads, etc), that no productivity difference is found between male and female scientists. Female scientists are, on average, less likely to have as many resources as male scientists as they are more likely to take positions with heavier teaching loads. How to reconcile the CV studies showing discrimination and the correlational evidence suggesting none? In an excellent analysis of the Ceci and Williams paper, Alison Gopnik asserts a possible hypothesis: "Women, knowing that they are subject to discrimination, may work twice as hard to produce high-quality grants and papers, so that the high quality offsets the influence of discrimination".

It's possible. But Gopnik also admits that it is also possible that policy changes could be responsible. In other words, that affirmative action-style policies that give women advantages could counteract the subconscious gender discrimination seen in the CV studies.

There's a darker side to these policies, though. Some worry about the discounting of a female professor's abilities, assuming she rose to the position via policy rather than talent. Furthermore, some policies designed to given women more voice actually end up give them more work - if a certain number of women need to be on a committee, then female professors are doing more service work than their male counterparts.

And then there's the matter of why female faculty find themselves in low-resource situations to begin with. Stated eloquently by Gopnik, "the conflict between female fertility and the typical tenure process is one important factor in women's access to resources. You could say that universities don't discriminate against women, they just discriminate against people whose fertility declines rapidly after 35."

And well-meaning policies also interact with the fertility issue in insidious ways. For example, many universities offer to "pause" the tenure clock for a year for a faculty member who gives birth before tenure. Sounds great, right? It could be, except that there is a tremendous amount of pressure to not take this credit for fear of seeming weak. This is especially true in departments that have faculty members who have already chosen not to take the time.

So... we have unconscious discrimination, conscious policies to counter said unconscious discrimination, conscious and unconscious backlash against the policies, and a structural problem for female fertility. In other words, it's a complicated picture and I don't know what the answer is. I do, however agree with Shankar Vedantam's assessment: "It is true that fewer women than men break into science and engineering careers today because they do not choose such careers. What isn't true is that those choices are truly "free.""

Monday, December 6, 2010

Book review: Addiction: A Disorder of Choice by Gene Heyman

I was apprehensive about reading this book. I was worried that it was going to be a hyper-conservative and moralizing tome. What I found instead was a provocative and well-researched book that I highly recommend to anyone interested in addiction, public policy or psychiatry.

As is clear from the book’s title, Heyman asserts that the dominant paradigm of drug addiction (that it is a “chronic and relapsing brain disease”) is not correct, and that by viewing addiction as the result of a series of willful actions, we have a better understanding of the course of drug addiction and its treatment.

Why is this view controversial? It strikes at the heart of the paradoxical way that we view drugs and drug addiction in the modern US. Heyman explains: “The reasoning behind this view is that if addiction is a disease, then science will soon find an effective treatment for it, as had been the case for many other diseases, but if that addiction is a matter of choice, then the appropriate response is punishment… The core assumption of this viewpoint is that there are but two possible responses to addiction: treatment or punishment”. As a good liberal, I was uncomfortable starting the book because I was worried that Heyman would be blaming the victims of addiction, and potentially creating policy that would take away treatment options, leaving them worse off.

Heyman remains unfortunately agnostic on what ought to be done about drug abuse, but focuses instead on the science and history of drug abuse and drug policy. Here are his central arguments for addiction being a choice:

The same drugs have different effects on people that depend on cultural context

Across time, culture and place, the reactions to the same drug are markedly different. If drug abuse were a biological reflex, this would not be the case. Of course, some of the “cultural contexts” listed by Heyman (smoking versus injecting heroin, for example) can dramatically influence the metabolism of the drug, which is a biological context that can influence receptor binding, etc.

The more interesting piece of this argument was that studying only those in treatment for drug addiction biases many studies of drug addicts. These people have higher co-morbidity with other mental illnesses and are more likely to relapse. For most people, a drug habit runs a natural course, beginning in a person’s late teens to early twenties and ending by age 30. Heyman profiles the majority population of invisible “successful addicts” who start and end drug-taking behavior as free choices.

The right motivations get just about anyone to quit

When people are given enough motivation, nearly all can quit taking drugs. 85% of drug addicted doctors and airline pilots faced with the possibility of passing all future random drug tests or losing their jobs will quit taking drugs. “Change your incentives, change your behavior, change your brain”.

The genetic basis for addiction is not compelling.

Heyman uses religiosity and twin studies to prove this point. Religion is a learned and voluntary behavior, and twins tend to have similar degrees of religiosity. However, the religiosity data only show a 0.3-0.4 correlation between even identical twins, so I agree with Heyman that the argument is a little weak.

The book misses a great opportunity to go into the neuroscience of addiction, as strengthening neural circuits associated with habit, and down-regulating neurotransmitter systems affected by the drugs could be very potent reasons why drug taking is so difficult to stop.

Near the end of the book is an argument of choice behavior, largely based on the very cool research of Drazen Prelec and colleagues. While it takes Heyman a while to set up the background, it is worth following as it has a lot of explanatory power for habitual behavior of all kinds, not just drug addictions. In brief, as the negative consequences of taking drugs accumulate slowly while the positive feeling of taking drugs is immediate (albeit diminishing over time), it takes a long-term perspective to see that drug-taking is a losing prospect in the long-term. The same goes with any bad habit: while just one cupcake will not cause you to gain 20 pounds, the habit of eating cupcakes over time will accumulate those 20 pounds. It takes a strong future orientation to see that the immediate deliciousness of the cupcake is not worth the long-term metabolic cost of the cupcake. Heyman refines his argument here by pointing out that while it is silly to say that someone would choose to be an addict, one becomes an addict from the accumulation of choices. “The point is that one day of heroin does not mean addiction, just as eating desert once does not make one fat. Of course as the days accumulate, the characteristics of addiction emerge, and as the deserts accumulate, fat cells get bigger”

One disappointment is the frequent straw-man argument along the lines of “It is not likely that anyone ever referred to recovery from obsessive compulsive disorder or schizophrenia as ‘going cold turkey’”. These arguments seem to appeal to the emotions behind addiction rather than the science. Also, cognitive behavioral therapy, which involves the willful changing of one’s beliefs and behaviors, is an effective strategy for combatting other mental illnesses such as OCD, only showing how nuanced the idea of will in mental illness really is.

Saturday, October 23, 2010

So, what makes you happy?

Research on the factors increasing or decreasing happiness has been of interest to psychologists and economists alike. Early research indicated that, contrary to our intuition, that major life events such as winning the lottery did not change our long-term ratings of our happiness. In other words, after a major life change, you will experience a temporary change in your happiness, but will return to being as happy as before the event. Such findings led to the set-point hypothesis that stated that each of us has an innate level of happiness, and that outside events, even large ones, don’t have a major influence on that set point.

Evidence for the set point hypothesis typically comes from longitudinal studies in which the same people rate their happiness each year, and report any major life events that occurred between surveys. From these data, you can correlate happiness as a function of the event by time-locking a sample population’s happiness the year an event occurs, and then seeing how it changes later. Let’s take marriage for example. Although each person in the sample gets married at a different time, the researcher can define year 0 to be the year of marriage for each person. Then, the researcher can look at this person’s happiness ratings both before and after marriage to determine the impact of marriage on happiness rankings. Below is the kind of graph that you get: planning and getting married makes people happy, and this happiness lasts for a couple of years, but after this, people go back to being however happy they were before.

Interestingly, although people hedonically adapt to marriage, they do not hedonically adapt to divorce. In other words, although marriage will not cause a permanent change in your happiness, getting a divorce will make you sadder in the long-term. Even more interesting is looking at the initial happiness ratings of people who marry and eventually divorce, and compare them to people who marry and stay married. It turns out that people who stay married were happier than their to-be-married-then-divorced friends even five years before marriage! This can be even before these people met their spouse.

Given that people do not strictly have one happiness set-point, what factors account for long-term changes in happiness? A new study in PNAS examines this question using 25 year longitudinal data from Germany. What I particularly enjoy about this study is that they focused on factors that people can control: although becoming disabled in an accident will likely lead to a long-term change in happiness, it is not something you can readily control. However, you do have control over things like your choice of romantic partner, your degree of religious involvement, your life priorities, whether you exercise, etc. Here is what they found:

- Focusing on money can’t buy you happiness. People who rated the acquisition of material goods as very important were less happy than people focused on family or volunteerism. Women whose partners were materially focused were particularly sad.

- You are less happy when you work more or (in particular) less than you would prefer to work.

- Being with friends and exercising regularly can make you happy.

- If you are a man, don’t be underweight. If you are a woman, don’t be obese.

- Choose a partner who is not neurotic.

- Although the study found a positive effect of religious participation, this is also correlated with altruism, family focus, and social participation, all of which independently increase happiness.

Although each of these factors had a small effect on happiness, all of them seem like good, common sense. I’ll go out for a run now.

Headey B, Muffels R, & Wagner GG (2010). Long-running German panel survey shows that personal and economic choices, not just genes, matter for happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107 (42), 17922-6 PMID: 20921399

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Subtle influences on choice

Like most people, I like to think that my choices are a result of clear, rational thought. However, our decision processes are far more heuristic than we admit. Two new articles on choice bear this out:

Mantonakis and colleagues studied how the order of items presented to us affects our preferences and choices. In their experiment, several wines were presented to participants to taste and rate. Although participants were told that all wines were from the same varietal (e.g. pinot grigio), in reality, all of the samples were from the exact same wine! If preference and ratings were rational, then the average rating a wine receives by subjects should be the same regardless of whether it was tasted first or last. However, they found that the first wine tasted by participants was preferred over wines in other serial positions, a finding known as the primacy effect.

In the second paper, Krajbich and colleagues modeled decision choices made by subjects between two pieces of junk food. Krajbick brought junk-food-loving, hungry participants into the lab, and asked them to rate how desirable 70 different junk foods are to them. Then, in front of an eye tracker, they were presented with pairs of pictures of these food packages and asked to decide which they would prefer to eat after the experiment. Unsurprisingly, people are quicker to decide when the value of the two choices is very different. However, when the decision is more difficult, participants tended to choose the item they looked at more.

Both of these studies are laboratory demonstrations of things advertisers seems to have known for a while: to get you to buy their product, getting you to look at it early and often might be enough to get you to buy it.

Mantonakis, A., Rodero, P., Lesschaeve, I., & Hastie, R. (2009). Order in Choice: Effects of Serial Position on Preferences Psychological Science, 20 (11), 1309-1312 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02453.x

Krajbich I, Armel C, & Rangel A (2010). Visual fixations and the computation and comparison of value in simple choice. Nature neuroscience, 13 (10), 1292-8 PMID: 20835253

Mantonakis and colleagues studied how the order of items presented to us affects our preferences and choices. In their experiment, several wines were presented to participants to taste and rate. Although participants were told that all wines were from the same varietal (e.g. pinot grigio), in reality, all of the samples were from the exact same wine! If preference and ratings were rational, then the average rating a wine receives by subjects should be the same regardless of whether it was tasted first or last. However, they found that the first wine tasted by participants was preferred over wines in other serial positions, a finding known as the primacy effect.

In the second paper, Krajbich and colleagues modeled decision choices made by subjects between two pieces of junk food. Krajbick brought junk-food-loving, hungry participants into the lab, and asked them to rate how desirable 70 different junk foods are to them. Then, in front of an eye tracker, they were presented with pairs of pictures of these food packages and asked to decide which they would prefer to eat after the experiment. Unsurprisingly, people are quicker to decide when the value of the two choices is very different. However, when the decision is more difficult, participants tended to choose the item they looked at more.

Both of these studies are laboratory demonstrations of things advertisers seems to have known for a while: to get you to buy their product, getting you to look at it early and often might be enough to get you to buy it.

Mantonakis, A., Rodero, P., Lesschaeve, I., & Hastie, R. (2009). Order in Choice: Effects of Serial Position on Preferences Psychological Science, 20 (11), 1309-1312 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02453.x

Krajbich I, Armel C, & Rangel A (2010). Visual fixations and the computation and comparison of value in simple choice. Nature neuroscience, 13 (10), 1292-8 PMID: 20835253

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)