Magnetic Pulses to the Brain Make it Impossible to Lie: Study

Zapping the brain with magnets makes it IMPOSSIBLE to lie, claim scientists

Holy crap! Hold on to your civil liberties...get your tin foil hat.... Something really exciting must be going on in neuroscience.

Right?

So it turns out that these articles refer to the following study:

Here, participants were shown red and blue circles and asked to name the color of the circle. At will, the participant could choose to lie or tell the truth about the color of the circle. However, while they were performing this task, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) was applied to one of four brain areas (right or left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), or right or left parietal cortex (PC)). TMS produces a transient magnetic field that produces electrical activity in the brain. As it is causing the brain to have different firing behavior, TMS allows researchers to gain insight into how certain brain areas cause behavior. Previously, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has been implicated in generated lies. Here, the authors sought to assess whether this area has a causal role in deciding whether or not to tell a lie. Here, the parietal cortex served as a control area as it is not generally implicated in the generation of lies.

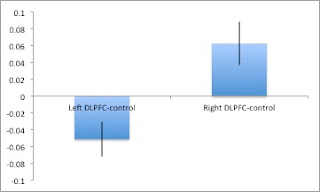

So, is TMS to DLPFC the new truth serum? Here, I've re-plotted their results:

When TMS was applied to the left DFPFC (compared with the left PC), participants were less likely to choose to tell the truth whereas they were slightly more likely to be truthful when stimulation was applied to the right DLPFC. As you can see from the graph, the effect, although significant, is pretty tiny. The stimulation changes your propensity to lie or truth-tell about 5% in either direction. This cannot be farther from the "impossible to lie" headlines.

Interesting? Yes. Useful for law enforcement? Probably not.

Karton I, & Bachmann T (2011). Effect of prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation on spontaneous truth-telling. Behavioural brain research, 225 (1), 209-14 PMID: 21807030

Showing posts with label causality. Show all posts

Showing posts with label causality. Show all posts

Monday, September 26, 2011

Monday, January 3, 2011

Is it time to question a lack of free will?

In the early 1980s, psychologist Benjamin Libet conducted a relatively simple experiment that critically shaped the way we think about free-will. Participants sat facing a clock, keeping a finger on a button, and were instructed to lift the finger whenever they pleased, remembering the clock time corresponding to the time when they decided to move the finger. All the while, EEG was being recorded. Libet found that 300-500 msec before participants moved (and about 150 msec before reporting that they decided to move), that a strong negative signal was found in the EEG waveforms. If the brain "knows" you are going to move before you do, do you really have conscious control over your own behavior?

The Libet experiment has been replicated, if not uncontroversial among philosophers. However, a new paper in Psychological Science questions whether the readiness potential is an artifact of observing a moving clock.

In the new study, Jeff Miller and colleagues presented participants with two decision-making conditions: a clock condition, similar to that of Libet, and a condition without the clock. If the time between the decision and the movement is constant, then one can look at the EEG from the time to move, with or without the clock. The authors found that participants in the clock condition showed the readiness potential, but the participants in the no-clock condition did not, suggesting that the act of monitoring the clock modulated the EEG signal, not the preparation for making a decision.

I think that this study is innovative as we need new methods to study the time course of decision making. I do think it asks more questions than it answers, though. For example, there are differences between the clock and no-clock groups that go beyond the presence of a clock: being asked to keep a time in mind provides a load to working memory that the no-clock participants did not have.

Is it time to give up on Libet? I'm not so sure. Is it time to reconsider with new methods? Absolutely!

Miller J, Shepherdson P, & Trevena J (2010). Effects of Clock Monitoring on Electroencephalographic Activity: Is Unconscious Movement Initiation an Artifact of the Clock? Psychological science : a journal of the American Psychological Society / APS PMID: 21123855

The Libet experiment has been replicated, if not uncontroversial among philosophers. However, a new paper in Psychological Science questions whether the readiness potential is an artifact of observing a moving clock.

In the new study, Jeff Miller and colleagues presented participants with two decision-making conditions: a clock condition, similar to that of Libet, and a condition without the clock. If the time between the decision and the movement is constant, then one can look at the EEG from the time to move, with or without the clock. The authors found that participants in the clock condition showed the readiness potential, but the participants in the no-clock condition did not, suggesting that the act of monitoring the clock modulated the EEG signal, not the preparation for making a decision.

I think that this study is innovative as we need new methods to study the time course of decision making. I do think it asks more questions than it answers, though. For example, there are differences between the clock and no-clock groups that go beyond the presence of a clock: being asked to keep a time in mind provides a load to working memory that the no-clock participants did not have.

Is it time to give up on Libet? I'm not so sure. Is it time to reconsider with new methods? Absolutely!

Miller J, Shepherdson P, & Trevena J (2010). Effects of Clock Monitoring on Electroencephalographic Activity: Is Unconscious Movement Initiation an Artifact of the Clock? Psychological science : a journal of the American Psychological Society / APS PMID: 21123855

Saturday, October 9, 2010

Did my brain make me do it?

Our first case is from a 40-year old man who developed a new and intense interest in child pornography. His sexuality also generally increased, and he found himself frequenting prostitutes even though he never had before. He was ashamed of his behavior and went to lengths to hide it, and could communicate that it was morally wrong. However, he then began making sexual advances on his pre-pubescent step-daughter and spoke of raping his landlady. He was removed from his home, but failed a 12 step sexual addiction program as he could not restrain himself from soliciting sexual favors from the staff and fellow group members. As he failed the program, he was sentenced to prison, but developed debilitating headaches and balance problems shortly before admission. An MRI revealed a large tumor in his orbitofrontal lobe, an area associated with self control, executive function and the regulation of social behavior. Following surgical removal of the tumor, the man was able to successfully complete the sexual addition course, successfully moved back in with his family and no longer had pedophilic or other deviant urges.

Consider, then our second case: the 1992 trial of Herbert Weinstein, a 65-year-old advertising executive who was charged with strangling his wife to death and then, in an effort to make the murder look like a suicide, throwing her body out the window of their Manhattan apartment. At his neuropsychiatric evaluation, it was found that Mr. Weinstein had a small, subarachnoid cyst in his brain. The defense moved to use this cyst as evidence of Mr. Weinstein’s inability to control, or be responsible for, his behavior. The cyst in Weinstein’s brain has never been linked to mental illness or violent behavior. After a contentious pre-trial hearing about using this evidence, Mr. Weinstein accepted a plea bargain.

Are both of these men equally responsible for their own behavior?

A central tenet of neuroscience is that all behavior is caused by the brain. This sounds simple enough, but given our long intellectual history of separating the mind from brain, we hold very dear to the idea of an “I”, separate from the 3 pounds of electrical meat that is our brain, calling the shots. After all, “I” feel like “I” make decisions that shape my life. If “I” wasn’t responsible for these decisions, if the decisions instead came from the electrical meat, which is determined by the laws of physics, then how is it that “I” decided to wear a blue shirt instead of the red one? More troubling, if “I” am just my brain, and my brain is malfunctioning, am “I” still responsible for my behavior?

People are remarkably consistent in their moral judgments. Therefore, with some confidence, I can predict that you feel that the man from case 1 is less responsible for his behavior than Mr. Weinstein from case 2. Is this gut-level feeling rational? After all, both men had damage to their brains, and their brains govern their behavior.

The problem with many cases of “my brain made me do it” arguments is that the association between a brain injury and a behavioral problem is not causal evidence that the injury caused the behavior. Another way of saying this is that “correlation does not imply causation”. We are quick to call B.S. on associations that don’t seem to have plausible causal connections: although drowning is associated with ice cream consumption, we do not guess that ice cream causes drowning. In the criminal realm, we are also likely to see through a Twinkie defense, even if “neuro-babble” makes for a more compelling case.

However, in the case of the first man, we are able to establish a causal connection between his brain injury and his bad behavior: he had “normal” behavior (presumably) before and after the tumor. Unfortunately, we cannot surgically repair most malfunctioning brains, so most connections between behavior and brain are speculative.

Beyond the problem of causality is the problem of will. How can we establish that someone absolutely cannot control his behavior? People can exhibit a certain degree of regulation over even autonomic functions using biofeedback or certain styles of meditation. In the lab, feedback from fMRI has been used to train subjects to willfully activate and de-activate a region involved in the perception of pain. However, it is incredibly difficult to willfully change most behaviors. It takes many days of consistent effort to form new habits. Many ex-smokers report that the physical withdrawal from nicotine was much easier to deal with than the reprogramming of one’s automatic response to grab a cigarette in various contexts. Although the politics of how we frame addiction is a larger topic for another post, suffice it to say that there is no consistent agreement what behaviors we expect people to be able to control, and those we don’t.

So, did my brain make me do it? Well, yes, of course it caused my behavior. Am I to be held responsible for this behavior? Given the above difficulties, I have to agree with Michael Gazzaniga who states that this question is to be left to the legal scholar and not the neuroscientist.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)